If you’ve been to Japan recently—or if you live here like I do—you might have noticed something’s changed.

Your favorite bowl of ramen? Now a bit pricier.

The convenience store bento? A little smaller, but somehow more expensive.

Even your Airbnb host might mention how high the electricity bills have gotten this summer.

I’ve lived in Japan for over 20 years. It’s always been a safe, stable country. But these days, there’s a quiet sense of unease in the air—something harder to explain.

・Groceries are quietly getting more expensive.

・School lunch fees have gone up.

・Gas and electricity bills are taking a bigger bite out of household budgets.

And every people are saying the same thing:

“Our paychecks haven’t changed, but everything else has.”

It’s not just about prices. It’s about uncertainty. People are starting to question where the country is headed, and whether anyone in charge is really listening.

Then, in July 2025, something happened that almost no one expected:

Japan’s ruling party lost its majority in the Upper House—for the first time in 15 years.

Yes, in a country known for political stability, this was a true political earthquake.

I’ve been living in Japan for more than two decades. And I can tell you—this election result didn’t come out of nowhere.

People didn’t just wake up and suddenly want change.

They’ve been living it. Feeling it. Day after day.

Let me explain what many of us here are experiencing right now!

2025 Japanese House of Councillors election

In July 2025, Japan held its latest House of Councillors election—and the outcome shocked many.

For the first time in 15 years, the ruling coalition—made up of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior partner Komeito—failed to secure a majority in the upper house of Japan’s parliament. This marks a major turning point in a country long known for political stability.

Japan’s national legislature, the Diet, has two chambers:

House of Representatives: chooses the prime minister and holds more power.

House of Councillors: reviews laws, budgets, and treaties.

Half of the 248 seats in the House of Councillors are contested every three years.

The LDP has dominated Japanese politics almost nonstop since the 1950s. Losing control of the upper house reflects a rare collapse in public trust—and a growing frustration with the political status quo.

But it wasn’t just the traditional opposition that gained.

Sanseitō, a conservative populist party that only entered national politics in 2022, surged to win 14 seats—becoming a symbol of Japan’s growing anti-establishment wave. Alongside other outsider groups, it drew support from voters tired of both the ruling parties and the conventional opposition.

This election signals not just a political shift—but a deeper public demand for change in how Japan is governed.

So, how did Japan—long seen as one of the world’s most politically stable countries—end up with such a dramatic shift in power?

To understand this, we need to look beyond the headlines and into everyday life in Japan right now.

From rising living costs to growing unease over immigration and social services, many voters feel that something fundamental is no longer working.

Let’s break down the key issues that pushed this election in such a surprising direction!

💸 Prices soar, pay stays poor

Everyone talks about it quietly—on the train, in line at the supermarket, at school meetings.

Groceries cost more than they did last year.

Utility bills keep rising.

Public services—from trash collection to school lunches—are quietly cutting corners or raising fees.

But wages? Still stuck.

now outprices my pork cutlet—

inflation bites hard.

At one supermarket in Japan, shoppers came across this playful haiku posted near the produce section. What sounds like a joke carries real weight.

Vegetable prices, especially cabbage—have soared in recent months. And when even grocery store poetry turns to inflation, it’s a clear sign that the cost of living is no longer just a background concern. It’s part of everyday conversation.

The steep price increase caused many cabbages to remain unsold, as shown in the image. This highlights how soaring costs can backfire, reducing demand and leading to waste.

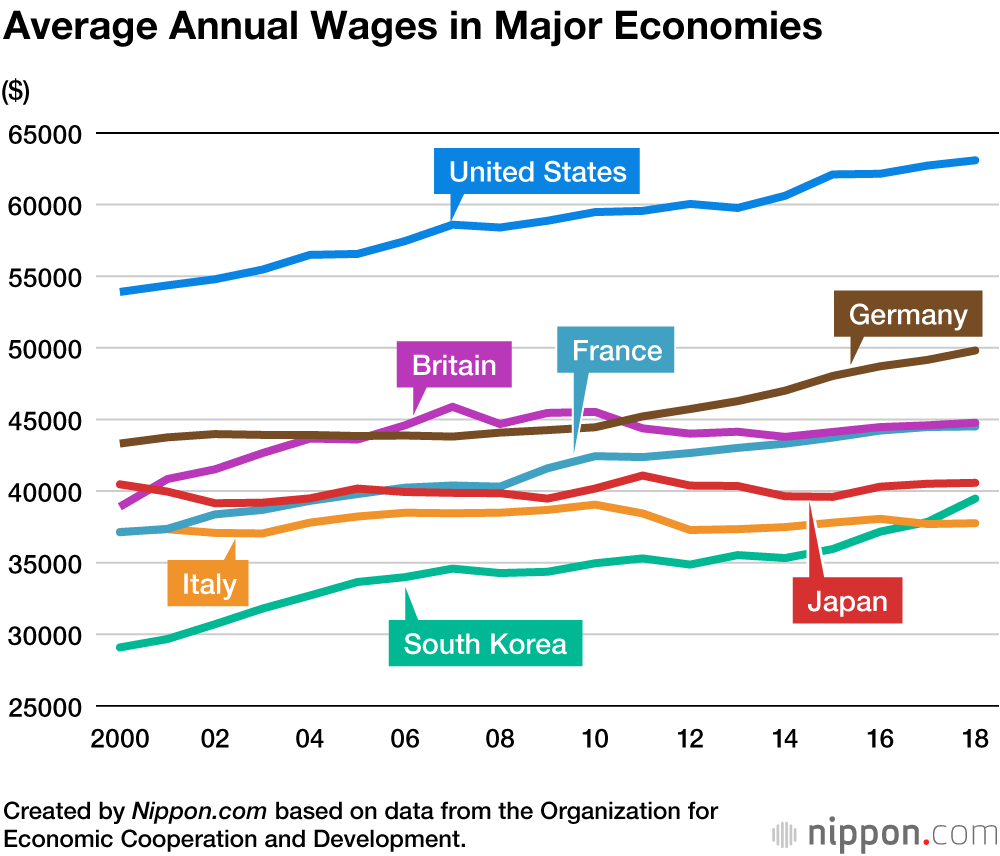

Image Source: “Average Annual Wages in Japan Remain Flat for Decades“ Nippon.com, April 2024.

Meanwhile, wages across Japan have barely increased overall. When you factor in rising prices as well as deductions like income and resident taxes, many people’s take-home pay is effectively shrinking, making daily life increasingly difficult.

This period of economic stagnation is often referred to in Japan as the “Lost 30 Years“. (失われた30年)

During this time, average wages barely increased, and one generation in particular—the so-called “Employment Ice Age generation“(氷河期世代)—faced especially harsh job prospects after graduating in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Their frustration, along with broader public dissatisfaction, has only grown in recent years as prices have spiked without meaningful wage growth.

As a result, tackling inflation and raising wages became key issues in the 2025 Upper House election. In a rare show of consensus, nearly every major party adopted some form of anti-inflation messaging in their campaign slogans—highlighting how urgent and widespread these concerns have become.

As of July 21, 2025, a poll on Yahoo! Japan’s “Everyone’s Opinion (みんなの意見)” asked users:

“What issue do you consider most important in this Upper House election?”

The overwhelming top answer, chosen by 57.2% of respondents, was “Economy and Fiscal Policy.”

Scrolling through the comments reveals a common thread:

Many expressed anger over Japan’s stagnant economy, criticizing the political establishment for “wasting 30 years” of potential growth. Others pointed to the consumption tax and income tax, saying it’s simply too high, especially when wages have barely changed in decades.

🧳 Overtourism

Japan reopened its borders after COVID—and tourists came flooding back.

Great for the economy? Sure. But for people living in places like Kyoto, Nara, or Tokyo’s Asakusa, daily life has become harder.

Trains are packed, streets are crowded, and local stores now prioritize tourists over regulars. “Overtourism” has become a real pain point, especially for older residents and working families who rely on public spaces and transport.

Beyond the general crowding, specific behaviors by some foreign tourists have caused frustration among local residents.

For example, at the famous Kamakura High School crossing, large groups of tourists often gather in the middle of the road to take photos, blocking traffic and causing safety concerns. In some shrines, tourists have been seen doing inappropriate things like hanging from the iconic torii gates.

In Kyoto, persistent tourists chase after Maiko—traditional apprentice geishas—trying to take photos despite repeated requests for privacy.

Littering and poor manners have also become common complaints, with many locals feeling overwhelmed and disrespected by these disruptions.

These issues have fueled growing calls among Japanese citizens for better management of tourism and respect for local communities.

On top of these challenges, the rapid increase in inbound tourism has led many restaurants to adopt tourist pricing.

For example, at the famous seafood stalls in Tokyo’s Toyosu Market, bowls of seafood that cost over 5,000 yen—and even premium seafood bowls topped with fatty tuna priced at 6,980 yen—have become common.

Social media users quickly nicknamed these dishes “Inboundon”(*インバウン丼) and the term went viral.

* Inbound” (referring to foreign tourists visiting Japan) + “Donburi” (a popular Japanese rice bowl dish)

Given Japan’s weak yen, some have even argued that such prices reflect “global standards,” and suggested that if Japanese wages rise, the higher costs might be more acceptable.

Some voters have noticed all this and are asking: Is the government doing enough to protect our quality of life?

🌏 Immigration and Integration problems

With Japan’s aging population, there’s an urgent need for foreign workers. More people from Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East are coming to fill gaps in healthcare, logistics, and construction.

But the social systems to support this change? They haven’t caught up.

Adding to public concern is the perception that immigration policies in Europe have failed to integrate newcomers effectively—something many Japanese citizens worry could happen domestically as well.

Image Source: “Foreign residents in Japan 2023” Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In Kawaguchi, some residents have grown frustrated with disruptive behavior and criminal incidents reportedly involving a small portion of the Kurdish community.

The term “Kurdo-car” (クルドカー)has emerged online in Japan to describe vehicles—often older luxury sedans—linked to a small number of Kurdish residents, particularly in Saitama, and associated with poor driving manners or traffic violations such as overloading.

Meanwhile, fears over China’s growing presence in Japan have intensified.

Many point to Article 31 of China’s National Defense Mobilization Law(中华人民共和国国防动员法第三十一条), which requires Chinese citizens and their affiliated organizations to cooperate with the government in times of emergency—even abroad.

This has led to widespread suspicion about large-scale land purchases and what some see as a form of “economic colonization.”

Public anxiety has also grown around rising crime involving foreign nationals, the difficulty of communication due to language barriers, and a perceived lack of integration efforts.

One symbolic flashpoint came in Nara Park, where some Chinese tourists were filmed hitting or kicking the sacred deer, which are protected by law. This sparked national outrage.

Former “troublemaking” YouTuber Hezumaryu took matters into his own hands, publicly confronting abusive tourists to protect the deer.

His actions drew support—and in July 2025, he was elected to the Nara City Council. His unexpected win was seen by many as a clear message. Despite his past and arrest record, locals are fed up with the negative side effects of unregulated tourism and poor immigration oversight.

While some of the party’s positions—such as strong anti-vaccine rhetoric or an almost religious belief in organic living—may lack scientific grounding, the Sanseitō’s core message of “Japanese First” resonated deeply with many voters. Given the growing social and economic frustrations, its rise in popularity feels, to many, like a natural outcome.

🍚 Rice Crisis

In Japan, rice isn’t just a staple food—it’s cultural, spiritual, and central to daily life. But in 2025, something unthinkable happened: rice began to disappear from store shelves.

Unusually high temperatures, erratic weather, and severe droughts across key agricultural regions led to poor harvests. Combined with rising production costs and fertilizer shortages, the result was a sharp decline in supply.

Prices surged, and in some areas, shoppers were greeted with empty rice shelves or strict quantity limits. Some families turned to imported rice, while others began rationing or switching to bread and noodles.

For many Japanese, this wasn’t just an inconvenience—it felt like a loss of identity. Voters began asking: If even our rice isn’t secure, what is?

Conclusion

For decades, Japan was seen as a nation of quiet resilience—orderly, predictable, and stable. But beneath the surface, the pressure had been building. Rising costs, stagnant wages, overcrowded cities, shifting demographics, and a government that many felt was out of touch—these weren’t just policy failures. They were lived realities.

The 2025 Upper House election revealed what many had long felt: Japan is at a crossroads.

Whether it’s protecting daily life from the ripple effects of global tourism, rethinking how the country handles immigration, or simply ensuring that people can afford a bowl of rice, the public is no longer willing to wait patiently for change.

The political shake-up was not just about dissatisfaction—it was a demand for accountability, responsiveness, and new ideas.

What happens next depends not only on those in power, but on whether Japan’s leaders can truly hear the voices that brought them to this point.

One thing is certain: the old status quo is gone.

The question now is—what kind of future will Japan choose to build from here?