Imagine a ruler said to descend from the sun goddess herself — a monarch who, within living memory, was once revered as divine, only to be transformed by a single declaration, not into an ordinary man, but into a symbol.

That is precisely the Emperor of Japan.

To many outside Japan, the Emperor’s role may seem enigmatic — a blend of sacred ritual, ancient imperial lineage, and modern constitutional symbolism. Yet even within Japan, the Emperor remains a figure wrapped in paradox. He is a constant presence throughout Japanese history, but his meaning has shifted profoundly over time.

From ancient tribal leaders who served as spiritual intermediaries to the contemporary image of the Emperor as a ceremonial emblem of the nation, this role has continuously evolved — shaped by politics, belief, and the needs of the era.

Join me as we explore the history of the Japanese Emperor, from sacred shaman to divine sovereign and from powerless figurehead to unifying national symbol, and discover who the Emperor truly is and why he continues to hold significance today!

- Emperor Jimmu and the Imperial Origins

- From Sacred Medium to Sovereign Authority

- The Emperor in Shadow

- The Divine Returns to Power

- From Divine to Symbol

Emperor Jimmu and the Imperial Origins

In the misty dawn of Japan’s recorded history stands Emperor Jimmu, said to have claimed his throne around 660 BCE. He was a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu,

Though historians now view this tale through the lens of mythology rather than fact, these ancient stories serve a deeper purpose—they weave all emperors into a single, unbroken thread stretching back to the gods themselves.

It’s dedicated to Amaterasu, and ancestral deity of the Imperial family.

Before Japan became one, the land was a patchwork of territories called kuni (クニ), each with its own identity.

During the Yayoi era (900 BCE-300 CE), these lands were guided by chieftains who held both sacred and secular authority in their hands. Chinese chronicles speak of a mysterious Queen Himiko, who in the 3rd century CE ruled the domain of Yamatai not through the sword, but through communion with the spirit world.

As the great burial mounds of the Kofun period (300-538 CE) rose across the landscape, they marked the gradual binding together of these separate realms. Later, in the Asuka era (538-710 CE), the visionary leadership of Empress Suiko and Prince Shōtoku brought forth transformative reforms, including the embrace of Buddhism that would forever alter Japan’s spiritual landscape.

Prince Shōtoku addressed the letter to Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty, asserting Japan as an equal sovereign state rather than a subordinate.

Accounts of the Eastern Barbarians (東夷傳俀國傳)

This marked a clear departure from China’s traditional Sinocentric worldview, in which the emperor was regarded as the sole ruler of the civilized world and surrounding nations were seen as vassals.

Japan’s bold phrasing symbolized its independent identity and rejection of the Chinese tribute system.

The Taika Reforms of 645 CE, like a strong current reshaping the shoreline, introduced a centralized system inspired by China’s imperial model. This culminated in the ritsuryō legal codes—the first formal architecture of imperial power.

The early Yamato rulers carried the title Ōkimi (大王) or “Great Kings”—figures who commanded armies and presided over sacred rites with equal authority. With skillful hands, they wove local clan deities into a tapestry of belief with themselves at the center, crafting unity from diversity.

Around the 7th century, like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis, a new title was born: Tennō (天皇), the “Heavenly Sovereign.” This transformation coincided with Japan finding its place within the broader East Asian world.

The ancient chronicles Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihon Shoki (720 CE) crystallized a profound idea—that the imperial family descended directly from Amaterasu, the radiant goddess of the sun.

This divine lineage elevated the emperor above all other clans, not merely as a ruler of men but as a bridge between heaven and earth. What had begun as tribal leadership had transformed into divine sovereignty, creating an institution that would weather the storms of more than a thousand years.

From Sacred Medium to Sovereign Authority

By the 4th and 5th centuries, like scattered raindrops forming a stream, political power began to concentrate in the verdant Yamato basin (present-day Nara Prefecture).

The rulers of this emerging center came to be known as Ōkimi—Great Kings who balanced the art of war with the power of ritual.

Though not yet bearing the title “Emperor,” these Ōkimi were undeniably sovereigns—mortal rulers who governed through alliance and sacred authority rather than divine mandate.

They were revered not as gods walking the earth, but as skilled leaders who bound the clans (uji) together under shared rituals and central governance. Their power flowed from both practical leadership and spiritual connection, but had not yet been touched by divine light.

The 7th century witnessed a transformation as profound as the changing of seasons—the birth of the title Tennō, “Heavenly Sovereign.” This shift bloomed amid Japan’s growing self-awareness, as its ruling elite sought to define themselves against the powerful cultural tides of China and Korea.

During this period of awakening, two monumental texts took shape: the Kojiki (712) and the Nihon Shoki (720).

Like master artisans, the compilers of these chronicles sculpted a narrative that traced the Emperor’s lineage directly to Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. From this moment forward, the Emperor was transfigured—no longer merely a leader of people, but a living connection between the realms of heaven and earth.

This divine narrative served as both anchor and sail for the imperial house, elevating it above rival clans and securing its place at the heart of Japanese identity. The Emperor now stood not just as sovereign but as sacred presence, the foundation upon which all political legitimacy rested.

The Emperor in Shadow

Despite this elevation to divine status, like the sun passing behind clouds, the Emperor’s actual power soon waned.

Beginning in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), real authority flowed into the hands of the shoguns—military leaders who governed Japan in the Emperor’s name while keeping him distant from the levers of power.

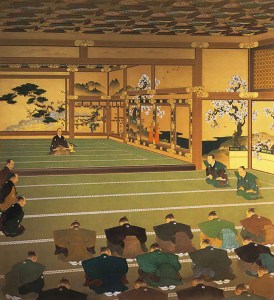

The Emperor remained in Kyoto like a treasured heirloom, tending to court ceremonies and preserving cultural traditions. Though deeply respected, he held no true sway over matters of state.

As a result, traditional court culture was preserved at the imperial court, where cultural activities such as poetry, gagaku music, and tea ceremony flourished.

During this long twilight, the Emperor became more symbol than sovereign—a revered bloodline rather than a ruling force.

This arrangement persisted across centuries.

Even during the ordered calm of the Edo period (1603–1868), when the Tokugawa shogunate ruled with an iron certainty, the Emperor remained a figure glimpsed through veils of ceremony. The divine aura lingered, but in truth, the Emperor lived as a guardian of tradition rather than a shaper of destiny.

- The Tokugawa shogunate was based in Edo to hold political and military power.

- The emperor remained in Kyoto as a symbol of historical tradition, culture, and spiritual authority.

By dividing these roles, the shogunate was able to govern the country more effectively.

The Divine Returns to Power

Everything changed with the swift currents of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Japan’s rulers, confronted by aggressive Western empires, had no choice but to resolve to build a strong, modern state on par with Europe and America. They needed a single, unifying symbol to inspire loyalty and solidify national identity—so they turned to the Emperor.

Under the rallying cry of Fukoku Kyōhei (富国強兵, “Enrich the country, strengthen the military”), adopted in the early 1870s, the Emperor was elevated from a distant figurehead to the sacred heart of the nation.

This slogan, drawn from older Confucian ideals, became the guiding principle of policy and helped legitimize rapid industrialization and military reform.

It is said that during the Edo period, Japan’s economy was as strong as that of the contemporary European powers. However, in terms of military strength, Japan lagged behind Europe. As a result, the new Meiji government looked to the modernization models of France and Prussia, strengthening both its economy and military by adopting Western systems.

Modeled after the Constitution of Prussia, which emphasized strong monarchical power, it declared the Emperor as the sovereign with extensive authority.

The Meiji government merged Shinto with state authority in what later became known as State Shinto, using shrines and state-trained priests to reinforce the idea of the Emperor’s divine lineage.

Through education and ritual, the Emperor’s image was deeply embedded in the national consciousness.

Schoolchildren recited the Imperial Rescript on Education (教育勅語) like a prayer. This edict, drafted by Meiji leaders, outlined Confucian virtues—such as filial piety and loyalty—and served both to shape moral values and to reinforce loyalty to the Emperor and state.

By the time of World War II, amid the intensity of total war, some people came to genuinely believe that the Emperor was an arahitogami—a living deity in human form.

From Divine to Symbol

When Japan surrendered, the United States transformed Japan by force, aiming to prevent it from ever becoming a military threat again.

One of the most significant changes came with the 1947 Constitution, which stripped the Emperor of all political power. The Emperor was redefined not as a ruler, but as a symbolic figurehead—”the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people”, as it had been in the past.

Since that transformation, the Japanese monarchy has functioned as a symbolic institution, focusing on public duties, ceremonial appearances, and cultural stewardship. The Emperor now serves to unite rather than to govern—a figure both ancient and contemporary, touched by tradition yet walking in the modern world.

Photo sourced from HUFFPOST

The Emperor is neither simple ruler nor relic of bygone days. Rather, he stands as a living symbol whose meaning has shifted like sand with the tides of time.

At various moments shaman and king, god and ceremonial prisoner, nation-builder and constitutional symbol, the Emperor embodies Japan’s evolving soul. His role has always reflected the needs and spirit of each age: spiritual guide in tribal times, political leader in early kingdoms, cultural guardian under warrior rule, and divine father in the nation-building era.

Today, the Emperor stands as a unique bridge spanning Japan’s long and winding journey—a presence that exists in the fertile ground between myth and reality, between ancient divinity and modern democracy.

So, who, then, is the Emperor?

The answer is never singular. The Emperor is, and has always been, what Japan needed him to be—a mirror reflecting the nation’s changing identity across the flowing river of time.